The Simultaneity of Cause and Effect

Buddhism teaches that the law of cause and effect underlies the workings of all phenomena. Positive thoughts, words and actions create positive effects in our lives, leading to happiness. On the other hand, negative thoughts, words and actions—those that in some way undermine the dignity of life—lead to unhappiness. This is the general principle of karma.

In Buddhist teachings other than the Lotus Sutra, Buddhist practice is understood as a gradual journey of transformation that unfolds in accordance with this process of cause and effect. This is a process by which the essentially flawed and imperfect common mortal gradually transforms over the course of many lifetimes into a state of perfection—Buddhahood. It is an undertaking that requires painstaking efforts to accumulate positive causes while receiving the effects of past negative causes and avoiding new negative causes.

Existing Simultaneously

However, Nichiren Buddhism, which is based on the teachings of the Lotus Sutra, offers a very different view of the causality of attaining Buddhahood.

The difference between these two views is best explained through the concept of the Ten Worlds. This concept describes our inner state of life at any moment in terms of ten “worlds,” from hell to Buddhahood, which we move between constantly depending on how we live our life and respond to our environment.

In the pre-Lotus Sutra view, ordinary people carry out Buddhist practice in the nine worlds (cause) and eventually attain Buddhahood (effect). The nine worlds disappear completely, replaced by the world of Buddhahood. The Lotus Sutra, on the other hand, clarifies that Buddhahood and the other nine worlds are each eternally inherent possibilities of life at each moment. Through faith and practice, the world of Buddhahood, which is otherwise dormant, is brought forth and the nine worlds go into a state of dormancy, though they never completely disappear.

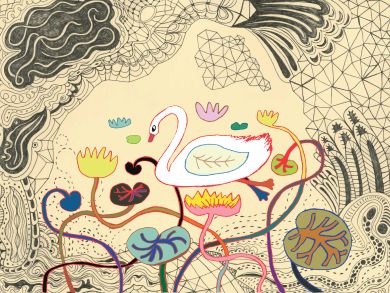

This revolutionary perspective on “attaining” Buddhahood is expressed in the concept of the simultaneity of cause and effect. The nine worlds (“cause”) and the world of Buddhahood (“effect”) are in fact equally inherent potentialities existing simultaneously in our lives. This concept is symbolized by the lotus plant, which, unlike other plants, bears flowers (symbolizing the ordinary person) and fruit (symbolizing Buddhahood) at the same time.

In other words, from the perspective of the Lotus Sutra, delusion and enlightenment—the ordinary person and the Buddha—are two aspects, or possibilities, that are always equally inherent in life. Our inability to perceive our inherent Buddha nature—the idea that Buddhahood is somehow remote from our ordinary reality—is simply a delusion, a result of negative causes that have accumulated in or lives over many existences. However, through the correct Buddhist practice, anyone can activate their Buddha nature.

Here and Now

The difference between these two views of Buddhahood could be described using the analogy of a video game. The conventional view of the process of enlightenment is like a game character who gradually overcomes an array of inherent flaws, accumulating various powers and useful tools while successfully passing through to the advanced stages of the game.

In the Lotus Sutra’s view of enlightenment, the game character is from the beginning already in possession of all the full powers possible, and only requires a means to unlock them.

The practice of Nichiren Buddhism is one of manifesting the potential of Buddhahood here and now.

Chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo with faith in one’s inherent Buddhahood could be compared to activating the “code” that unlocks this potential, revealing the wisdom, compassion and courage needed to surmount obstacles as they arise.

Human beings, we could say, possess the DNA for becoming Buddhas, which is activated by chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo.

The practice of Nichiren Buddhism is one of activating the qualities of our inherent Buddha nature here and now, in the midst of our ordinary daily lives. In real terms this means that when we harness the power of the world of Buddhahood inherent within us, we can surmount any difficulty and establish a happy and victorious path of life.

As the fundamental orientation of our life becomes one of hope and compassion, even our weaknesses and failings can function positively, becoming a source of understanding and thoughtfulness toward others. This does not mean, though, that we completely and finally transcend our capacity for delusion.

Bringing forth one’s enlightened nature—characterized by courage, wisdom, compassion and life force—we are then equipped to engage fully with the problems of life, change reality for the better and make enlightenment an actuality.

Problems and challenges, in this sense, serve as a means for us to demonstrate the strength and reality of inherent Buddha nature and to inspire others to do the same. Buddhism is about living confidently and expansively here and now. The key component in this is faith in our Buddhahood.

When we have full confidence in our Buddha nature and our ability to transform and triumph over any kind of suffering, problems become challenges to be welcomed rather than avoided. This sustained sense of confidence and determination in the face of difficulties is itself a manifestation of our Buddha nature and, in accordance with the principle of the simultaneity of cause and effect, assures our success in life.

Adapted from an article in the April 2013 issue of the SGI Quarterly.