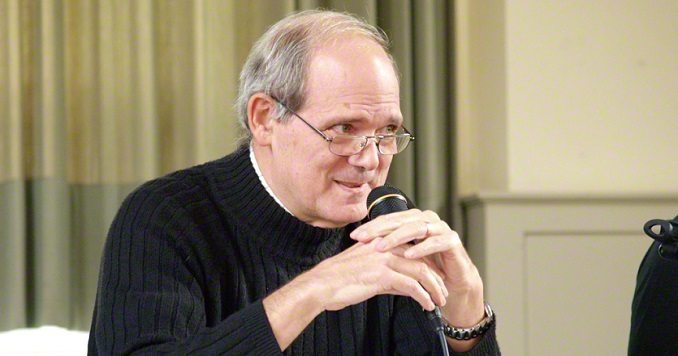

Rediscovering Your Way: Dennis Gira on the Value of Interreligious Dialogue

Dennis Gira, former assistant director of the Institute of Religious Studies (l’Institut de science et de théologie des religions) at the Catholic University of Paris, is a French theologian and specialist in Buddhist studies. In this interview in the December 11, 2020, issue of the Seikyo Shimbun, the Soka Gakkai’s daily newspaper, he discusses why he has devoted himself to the study of Buddhism, the value of interreligious dialogue and the French translation of the Gosho (The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin).

You are a Catholic theologian, but also a specialist in Buddhism. What importance do you accord to your simultaneous study of two religions?

I am not the only one. In recent years, many Catholic theologians have begun to study Buddhism seriously. This is undoubtedly largely due to the impetus given by the Fathers of the Second Vatican Council 1 who, within the framework of the reform and the modernization of the Church envisioned by the Council, emphasized the necessity of interreligious dialogue. It is worth noting that Protestants have also been involved in promoting the dialogue with and the study of Buddhism.

When a believer of one religion tries to understand the faith of someone who believes differently and desires to dialogue with him or her, it is essential that both of them be ready to go as far as possible in their research of the deepest meaning of their own faith and of the faith of their partner in dialogue. In this way, they will each return to the initial spirit of their respective founder’s experience and teaching.

By continually making efforts to familiarize ourselves with the “summit” of other religious traditions through dialogue, we will be able to open up deep heart-to-heart communication.

To avoid all confusion here, I should explain that I study two religions, but the only Way that I follow is that of Jesus Christ. And what I evidently expect of my Buddhist partners in dialogue is that they also study both traditions and that the only Way they follow be that of the Buddha.

The “Way of Christ” and the “Way of Buddha” have many things in common, and those who follow one or the other of these paths can share certain values and carry out many works together, without thinking in terms of a conversion from one religion to the other. It is clear that the Good Samaritan [in the Biblical parable], though considered as an enemy by many linked to the Temple in Jerusalem, followed the Way indicated by Jesus, much more so than the priests and other religious leaders who were, like Jesus, practicing Jews. For Christians, non-Christians who behave as the Samaritan did—that is to say coming to the aid of those who are in need—walk concretely on a Way close to the one Jesus indicates to his disciples, much more so than Christians who do not behave as the Samaritan did.

The French writer Albert Camus stated that “Honesty consists in judging a doctrine by its peaks, not by its by-products.” What do you believe he meant by this?

Someone who speaks about Christianity only in terms of the crusades and colonization, etc., would be talking about only the negative by-products of this tradition, giving a limited or even false interpretation of its true meaning. It would be like speaking of Japanese Buddhism in terms of the warrior monks of bygone days. The history of these two traditions cannot, in all honesty, be reduced to these by-products. But when we look toward the heights of a religion, where its fundamental meaning is to be found, we inevitably discover its true spiritual dimension that is capable of contributing to the well-being of human beings.

Encounters and dialogues with people from different social contexts, with value systems very different from our own, are privileged opportunities to discover common ground.

By continually making efforts to familiarize ourselves with the “summit” of other religious traditions through dialogue, we will be able to open up deep heart-to-heart communication. Understanding the summit of the faith of others also helps us deepen our own faith. In this sense, it becomes clear that for a religion that wants to be open to the world, the spirit and the practice of dialogue are indispensable.

This principle applies not only to religion but to all aspects of life. Encounters and dialogues with people from different social contexts, with value systems very different from our own, are privileged opportunities to discover common ground. At the same time, they are an opportunity to become more deeply conscious of our own specificity, of our unique “talents” that are never exactly the same as those of others, and also of our strengths. The result is that, through dialogue, we can develop and become better people.

You have helped introduce Nichiren Buddhism more deeply into French society, beginning with your crucial contribution as supervisor of the French translation of the Gosho (The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin).

My study of Nichiren Buddhism and my collaboration in the work of translating the Gosho strengthened my conviction that every effort to understand the faith of others helps me, at the same time, to grow in my own faith. In this work, I wanted to emphasize that what is most important to an understanding of Nichiren is not listening to the rumors that circulate concerning him—what is said about him—but listening attentively to what Nichiren himself wanted to transmit, and that is to be found in his writings.

To illustrate this point, it is interesting to reflect that there are some who, on the basis of his very strong, even violent, arguments, reject Nichiren, accusing him of being “intolerant.” However, one should not forget that Nichiren lived and taught during the period of the Latter Day of the Law (Jpn. mappō). If the acute sense of the urgency of the situation that this gave Nichiren is not taken into account, it will be impossible to understand the passion with which he wanted to lead all beings to enlightenment. It was in thinking deeply about this context that I started to see that Nichiren’s use of the method of shakubuku [refuting provisional Buddhist teachings] reflected his desire to exercise the greatest compassion conceivable for a Buddhist and help people living during the dreaded circumstances of mappō attain enlightenment, at a time when this should have been impossible.

When Nichiren became conscious of the implications for people living in the Latter Day of the Law, he set out in search of the “king of sutras,” going to study in the great centers of research located in Kyoto, Nara and elsewhere. His search led him to the Lotus Sutra. This sutra conveys two fundamental truths: (1) the Buddha nature is the profound inherent nature of every living being; (2) the Buddha is eternal and has been leading beings since the “beginningless past.” But many of his followers, also living in the Latter Day of the Law, completely forgot their identity—that of being the Buddha’s children and heirs. This is why the parable of the wealthy man and his poor son in the Lotus Sutra is so telling.

The magazine Le Monde des religions asked me to write an article to help readers understand the importance of the Lotus Sutra exhibition that was held at UNESCO Headquarters in Paris (in April 2016). After long reflection, I decided to highlight three similarities that exist between this text and the Bible, as a way of offering potential visitors to the exhibition some keys to an understanding of the nature and importance of the teaching in the Lotus Sutra.

The first is the way both the Sutra and the Bible reveal astonishing things that had been hidden until then. In the 16th chapter of the sutra, “The Life Span of the Thus Come One,” for example, the truth about the original enlightenment of the Buddha, and thus the truth about his eternal existence, is made known. The Bible, for its part, reveals equally astonishing truths concerning the origins of the world, the human condition and, in Jesus Christ, God’s way of being among human beings.

The second affinity is the universal posture of the Sutra and of the Bible. This is reflected in the expectation of enlightenment (in the Sutra) and of salvation (in the Bible) that excludes no one. The position affirmed in the Lotus Sutra is founded on the conviction that all beings possess the “Buddha nature”; in the Bible, it is in the confidence in the fidelity of God to his creation, in his expressed will that all beings be saved and in the accomplishment of everything in the Risen Christ.

The third affinity is the ample use of parables by the Buddha in the Lotus Sutra and by Jesus Christ in the Gospels. The parable of the wealthy man and his poor son in the Lotus Sutra and that of the prodigal son in the Gospel according to Luke (Lk 15, 11–32) speak respectively, with eloquence, of the compassion of Buddha and of the mercy of God. These parables are extraordinary, reflecting the internal coherence of Buddhism and Christianity. At the same time, they show both the convergences and divergences of these two traditions. And that opens wide spaces for dialogue.

Keeping in mind these affinities, it is very important to respect the fundamental differences between these two parables, and the traditions they represent, and also to see that these differences can be put in service of developing a more exact understanding of the ineffable mystery of life. In this way, we will all be able to move more freely, fearlessly, within the spaces of dialogue offered to us, with the assurance that all who take part in such dialogue will be spiritually enriched.

By inheriting and transmitting from generation to generation the open-mindedness that is reflected in interreligious dialogue, religions can manifest their true value.

I agree. In every religion that is universal and open to the world there are always young people and new generations who embrace the heritage faithfully and, inspired by their respective traditions, live their spirituality faithfully and powerfully.

I watched, live, the Soka Gakkai virtual World Youth General Meeting of September 27, 2020 (in France it started at 5:30 in the morning!). These young people succeeded in communicating and sharing their feeling of “togetherness,” transcending the limits of physical distance. I found that very moving. I also reflected, with a sense of great hope, that these young people, with others like them from many different religions, embody the future of humankind.

They expressed—from country to country, via the Internet—their determination to light a torch for the world, affirming that Nichiren Buddhism is nothing other than a “Buddhism of the Sun” capable of “driving out the darkness of all beings.” Moreover, this image of light is also absolutely essential for Christians.

When I was young (long ago!), I was impressed by a Christian youth movement that had as its motto, “It is better to light a candle than to curse the darkness.” Indeed, even when we are not in a position to take actions that could have an immediate impact on the world, it is sufficient to begin with small things. While watching this World Youth General Meeting in September, the memory of this motto came back vividly. Even if the flame of a candle is miniscule, when each one of so many young people in the world light one, all together, the final result will clearly constitute a very great light for the world.

The young people taking part in the World Youth General Meeting often repeated the words “I have a dream.” Memorably, Martin Luther King often repeated these words throughout the vicissitudes of his life and especially during one of his most important addresses that became a call to all Americans: “I have a dream!”

To dream, that is the privilege of young people. This signifies that they are ready to commit themselves enthusiastically to facing the challenge of changing the world, dreaming that it can be better, convinced that the future will be one of justice, of solidarity and of peace.

- *1The ambition of the Second Vatican Council that took place between 1962 and 1965 was to help the Catholic Church adapt itself to the modern world. It called upon Catholics to be open and drew their attention to the importance of dialogue with that world and with the believers of other religious traditions