Shakubuku: Sharing the Essential Teaching of Buddhism

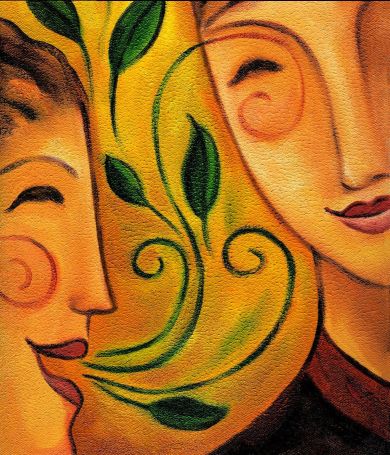

The purpose and goal of Buddhism is people’s happiness. The inner life of each of us is rich with untapped possibilities, deep spiritual reserves of wisdom, courage, energy and creativity. The unique beauty and wonder of each human being is that we give form and expression to these potentialities in endlessly varied ways, according to the particularities of our character, culture, personality and passion. The aim of Buddhism is to enable people to become aware of and bring forth the boundless potential of their lives. Buddhism refutes the sense of powerlessness we may feel in the face of suffering and new challenges, enabling us to tap our inner resources to transform any source of suffering and find fulfillment and purpose.

Within the broad tradition of Buddhism, it is the Lotus Sutra that most clearly defines this profound potential and clarifies that it exists equally within the lives of all people. It emphasizes that the purpose of Buddhist teachings is to enable all people to connect with that in the here and now. The Lotus Sutra is also notable for its “one vehicle teaching,” which embraces all and expresses the ultimate truth of Buddhism—that all people can attain Buddhahood and have the right to be happy.

Buddhist texts describe two basic methods of expounding this truth. The first, termed shoju in Japanese, is to share this view of life without directly challenging the other person’s existing beliefs. The second, shakubuku, is a more assertive expression of the truth and a challenge to views which diminish human life.

Shakubuku is a practice for others, a concrete exercise of compassion and belief in their Buddha nature.

Shakubuku is a practice for others, a concrete exercise of compassion and belief in their Buddha nature. It is an act of the highest respect for others and one that requires courage—to speak in-depth about the teachings of Buddhism. Practicing solely for oneself might seem an easier option, but this is not the real road to enlightenment.

By the 13th century, some 1,500 years after the death of Shakyamuni, Buddhism’s founder, Buddhism had become well-established in Japan but had split into numerous contending schools, each claiming to represent the true teaching of Shakyamuni. Some had also become co-opted into the existing oppressive and corrupt power structures.

It was in this context that Nichiren (1222–82), the founder of the Buddhism practiced by members of the Soka Gakkai, lived. After long study of the various Buddhist teachings, he began to vigorously refute those doctrines that he saw deviated from the life-affirming teachings of the Lotus Sutra. He continued to do this in the face of severe persecution from the established powers, out of his conviction that misguided philosophies which encouraged passivity and a sense of human powerlessness were the primary cause of suffering and social discord.

The portrayals of Nichiren’s famously impassioned efforts have sometimes obscured the fact that shakubuku is first and foremost about open dialogue. Nichiren always remained committed to dialogue, declaring, “So long as persons of wisdom do not prove my teachings to be false, I will never yield.” His opponents, refusing to risk debate, instead plotted his persecution.

The Lotus Sutra itself provides a model for shakubuku in the person of Bodhisattva Never Disparaging, who would bow deeply before each person he encountered, telling them he deeply revered them because they possessed the Buddha nature. His actions, however, were initially met with ridicule and aggression. Directly addressing the Buddha nature of others, what Bodhisattva Never Disparaging ultimately refuted in the people he encountered was their limited view of themselves.

It is a natural tendency to put limits on what we believe we are capable of and what we can expect out of life. In a sense, these walls are the means by which we define ourselves. We can easily become caged in by narrow views of our self and the world, and it can be uncomfortable and even threatening when this limited sense of our self is challenged. Buddhism continuously challenges our understanding of who we think we are.

The spirit of shakubuku, however, is never the shallow, argumentative concern with proving oneself or one’s views superior to another’s. It is the spirit of sustained compassion to enable another person to believe in the great, unrealized potential of their life.

Courtesy April 2011 issue of the SGI Quarterly.