Legacy of the Founding Presidents

-

[© Seikyo Shimbun]

[© Seikyo Shimbun] -

[© Seikyo Shimbun]

[© Seikyo Shimbun] -

[© Seikyo Shimbun]

[© Seikyo Shimbun]

The Soka Gakkai upholds a spiritual lineage that originates some 2,500 years ago with Shakyamuni and has been continued by Buddhist teachers in India, China and Japan, reaching its most profound expression in the teachings of Nichiren (1222–82).

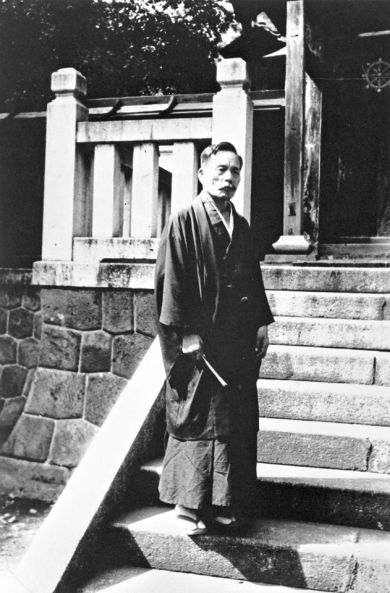

The first three presidents of the Soka Gakkai, Tsunesaburo Makiguchi (1871–1944), Josei Toda (1900–58) and Daisaku Ikeda (1928–2023), revived Nichiren Buddhism in the modern age and created the basis for its development as a globally accessible philosophy. Their shared commitment to this effort exemplifies the mentor-disciple relationship in Buddhism.

Makiguchi, Toda and Ikeda are respected as the founding presidents and mentors of the organization, enduring examples of how to practice and disseminate the teachings of Buddhism for the sake of peace. As such, they are referred to by the honorific title of “Sensei.”

Tsunesaburo Makiguchi (1871–1944) was a Japanese educator, geographer and philosopher who developed a unique pedagogy based on his own theory of value. Makiguchi believed that the ultimate objective of life could be best expressed in the word “happiness,” and that this should be the goal of education. He defined happiness in terms of the ability to create value: to affect a positive transformation in one’s reality.

Makiguchi eventually concluded with strong conviction that Nichiren Buddhism, which aims to realize a flourishing society where all people are happy, was in fact the key to achieving the ideals he had been pursuing through his value-creating education.

In 1930, together with his protégé Josei Toda, Makiguchi established the Soka Kyoiku Gakkai (Society for Value-Creating Education), later named the Soka Gakkai. What began as a society for reformist educators soon developed into a broad-based organization exploring the practical transformative effects of Buddhist practice. As a religious group it was atypical, being focused on small-scale discussion meetings among practitioners, rather than religious rituals and the authority of priests.

During World War II, Makiguchi and Toda were imprisoned as “thought criminals” by the Japanese militarist government, which aimed to suppress freedom of religion and expression. Makiguchi died in prison on November 18, 1944, having refused to the last to recant his beliefs.

Josei Toda (1900–58) was an educator, publisher and entrepreneur. Toda was responsible for realizing the publication of his mentor Makiguchi’s seminal work, Soka kyoikugaku taikei (The System of Value-Creating Pedagogy). Its publication on November 18, 1930, is today taken as the founding date of the Soka Gakkai.

Whilst in prison during World War II, Toda experienced two profound awakenings. The first was his realization that “the Buddha is life itself.” The second was an awakening to his identity as a Bodhisattva of the Earth whose life purpose was to spread the essential teachings of Buddhism. These realizations, together with Toda’s determination to eradicate misery from the world, became the impetus for his powerful efforts to develop the Soka Gakkai following his release from prison.

In the space of a little more than a decade, Toda built a dynamic organization of over 750,000 households in Japan. His ability to translate complex Buddhist concepts into clear, practical guidance helped thousands of people struggling amidst the postwar devastation to rebuild and find purpose in their lives. Toda’s concept of human revolution, the transformation of one’s own state of life, became a guiding principle for members’ practice. This framed the otherwise abstract idea of the attainment of Buddhahood as a self-motivated change in one’s inner life that creates a transformation in one’s circumstances and in society as a whole.

Toda was ardently opposed to war and the existence of nuclear weapons, and his 1957 Declaration Calling for the Abolition of Nuclear Weapons is seen as the starting point of the organization’s peace movement.

Daisaku Ikeda (1928–2023) was a youth of 19 searching for meaning in the devastation of postwar Japan when he encountered Josei Toda. Moved by Toda’s character, Ikeda decided to take him as a mentor and begin practicing Buddhism. As a youth leader in the organization, Ikeda led a number of successful campaigns that dramatically expanded the membership and were instrumental in enabling Toda to reach the milestone of 750,000 households.

In 1960, Ikeda succeeded Toda as third president and, as well as continuing to solidify and expand the organization within Japan, immediately began to focus on its internationalization. The founding of the Soka Gakkai International (SGI) in 1975 cemented this process. He also rapidly actualized other aspects of Makiguchi and Toda’s vision, including the establishment of the Soka School system and Soka University.

Ikeda further expanded the scope of the international association, developing it into a broad-based movement promoting peace, culture and education. Championing dialogue as the basis of peace, he began holding discussions with leaders and cultural figures around the world, collaborating with several to publish dialogues. He also established institutions promoting dialogue, peace research and cultural exchange.

A key aspect of Ikeda’s legacy are his prolific writings aimed at enabling individuals in the modern world to grasp and put into practice the empowering teachings of the Lotus Sutra and Nichiren. These include the 12-volume series The Human Revolution and 30-volume series The New Human Revolution detailing the historical development of the Soka Gakkai through stories of individual members.

Read more about the lives of the founding presidents here