Creating a Wave of Change Toward a Century Without War

On August 1, 2025, Soka Gakkai President Minoru Harada issued the following statement commemorating the eightieth anniversary of the end of World War II.

This year marks the eightieth anniversary of the end of World War II, a total war that engulfed the populations of countless nations. It is estimated that the casualties—well in excess of 60 million people—accounted for more than 3 percent of the world’s population; the vast majority of the victims were civilians, including women and children.

I express my deepest sorrow for all those from every nation who lost their precious lives in the war, and, as a practitioner of Buddhism, I sincerely pray for their peaceful repose.

Regardless of nationality or ethnicity, the pain of losing beloved family members or loved ones is the same for everyone.

As a Japanese citizen, I would like to reaffirm my solemn pledge to work to build peace not only in the Asia-Pacific region, where Japan’s past actions caused such immense devastation and anguish, but throughout the world, guided by deep reflection on this history.

As we approach August 15, the date that marks the end of the war for Japan, I am reminded of the long poem “August 15—The Dawn of a New Day,” which third Soka Gakkai president Daisaku Ikeda composed in August 2001.

The war had had a heavy impact on President Ikeda’s life as a teenager: the family had twice seen their home destroyed, and the eldest of his brothers had lost his life on the battlefield. Now, in the first summer of the twenty-first century, he left behind a testament to his harrowing wartime experiences, in the following words:

Our home-life shattered,

our family tossed down

to misery’s depths. . .

But we were hardly alone,

countless people wept tears

of anguished suffering

and heaving grief.

Each year I greet

this day of August 15

my heart filled with outrage.1

President Ikeda also stressed in this poem that the unspeakable suffering endured by ordinary people had spread to every corner of the planet. Those who sought to lead, he declared, must never, for all eternity, forget what the people of the world had experienced during the war.

The origins of the Soka Gakkai’s peace movement lie in the struggle of our founding president Tsunesaburo Makiguchi and second president Josei Toda: despite oppression by the militarist regime, resulting in their imprisonment in July 1943, they remained steadfast in their commitment to peace and human welfare based on the respect for the dignity of all life, a central tenet of Nichiren Buddhism.

Wartime experiences also left an indelible mark on me personally. I was born in Asakusabashi, a downtown district in eastern Tokyo, in November 1941, just one month before Japan entered the Pacific War. I was three years old when, in the middle of the night of March 9–10, 1945, a storm of incendiary bombs rained down on the densely populated neighborhoods of the city, consuming entire areas in vast firestorms and claiming the lives of some 100,000 people. The horror I felt as my mother and I fled through the burning streets remains deeply etched in my memory to this day.

Since the end of World War II, while we have narrowly avoided the horror of a third world war, atrocities have been repeated time and time again. Even today, armed conflicts and hostilities continue in various parts of the world, including the ongoing and calamitous situations in Ukraine and Gaza. The rising civilian death toll and the worsening humanitarian crises are deeply concerning.

Regardless of nationality or ethnicity, the pain of losing beloved family members or loved ones is the same for everyone. The war affected people everywhere, and though in a different way, many around the world keenly felt a similar sense of loss and vulnerability during the COVID-19 pandemic of recent years.

My heart aches for those who have lost their lives and for the families left behind.

Hostilities between Israel and Iran that erupted in June to great international alarm have thankfully subsided, avoiding further escalation. Likewise, regarding the protracted conflict in Ukraine and the situation in Gaza, I sincerely hope that sustained dialogue and persistent diplomatic efforts by all relevant parties will result in the cessation of conflict and the opening of a path toward a lasting resolution as soon as possible.

The preamble of the Charter of the United Nations, which was established in 1945 reflecting the lessons of the two World Wars, contains the following pledge: “to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, which twice in our lifetime has brought untold sorrow to mankind.” Yet, how many countries have truly remained free from the scourge of war over the past eight decades? In this sense, the task of building the peaceful world envisioned by the Charter remains far from complete.

Friendship with Neighboring Countries

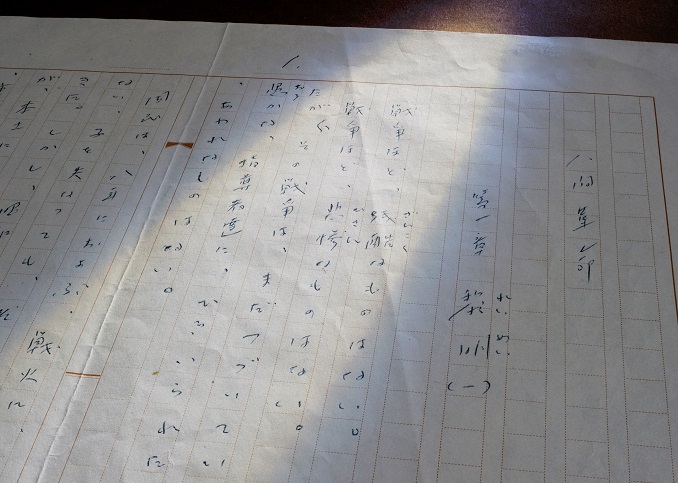

In December 1964, President Ikeda handed me a set of manuscripts—the first thirteen installments of the novel The Human Revolution to be serialized in the Soka Gakkai’s daily newspaper, the Seikyo Shimbun, where I was working as a reporter. This was a time when the Vietnam War, one of the deadliest conflicts since World War II, was beginning to escalate.

“Nothing is more barbarous than war. Nothing is more cruel.”

When I saw these opening words, which President Ikeda had written in Okinawa—the site of the fiercest ground battle in Japan during the war—I was struck by the depth of his indignation and outrage.

The newspaper began serializing the novel on January 1, 1965, and I was put in charge of tasks such as coordinating with the illustrator. Each day throughout this period, I keenly sensed, between the lines of his writing, President Ikeda’s profound resolve to build an unbreakable solidarity to open a path toward a world without war, no matter the obstacles.

My involvement in the project only continued for the first three volumes, but just before the serialization of the “War and Peace” chapter in Volume 5 began in April 1969, President Ikeda wrote the following passage in a magazine article:

“Among the numerous photographs depicting the quagmire of the Vietnam War, none is more heart-wrenching or compelling than the image of a mother and child fleeing to avoid gunfire. . .

“Had it not been for the war, they would likely have lived happy lives. So why, and for what cause, must that happiness be taken from them?”2

I vividly remember these words because the image of the mother and child in the photograph reminded me of what I myself had experienced and witnessed during the war.

At that time, President Ikeda repeatedly called for an immediate ceasefire in the Vietnam War and for the negotiation of a peace settlement, urging the international community to accelerate diplomatic initiatives to resolve the conflict. His tireless efforts to call for a swift end to the tragedy were always grounded in his profound awareness and concern, as one human to another, for the suffering people were enduring.

He offered prayers for the victims of war during visits to countries where Japan had inflicted unimaginable pain and hardship during World War II: Burma (present-day Myanmar), Thailand, Cambodia and India, which he visited in 1961, the year after his inauguration as the third president, as well as China, South Korea, the Philippines, Singapore, Malaysia and Australia. He dedicated his life to fostering friendship with these nations.

Unless we deeply reflect on past history at all times and constantly strive to build friendship with neighboring countries, the path toward world peace cannot be opened.

Through his dialogues with individuals from these countries, as well as Vietnam, Indonesia and other nations throughout the Pacific region, he sincerely bore witness to their testimonies about the atrocities committed by Japan during the war. He made continuous efforts to preserve each of their words for posterity by publishing them in Seikyo Shimbun articles and as dialogues in book form.

I had the privilege of observing his meetings with dialogue counterparts on multiple occasions and the honor of accompanying him on his first visit to China in May through June of 1974. As I prepared for the trip in my role as chief secretary of the delegation, President Ikeda taught me the conviction that unless we deeply reflect on past history at all times and constantly strive to build friendship with neighboring countries, the path toward world peace cannot be opened. Holding this conviction close to our hearts, we traveled via Hong Kong to Beijing, where, during a meeting with representatives of the China-Japan Friendship Association, he proposed concrete plans to promote exchanges between the youth and women of the two countries.

During his second visit to China in December of the same year he met with Premier Zhou Enlai. The Chinese premier, despite being gravely ill at the time, strongly expressed his wish to build a Sino-Japanese friendship that would last for generations. He also noted that President Ikeda had repeatedly emphasized the crucial importance of promoting friendship between the peoples of China and Japan; he declared that he was truly delighted by this. These two visits to China laid the groundwork for youth, cultural and educational exchanges between the two countries that continue to this day.

Upholding International Humanitarian Law

President Ikeda’s determination to build a world free from the tragedies of war, where all people everywhere can live in peace—clearly articulated in The Human Revolution—was inherited from second Soka Gakkai president Josei Toda.

I was among those present when President Toda issued his Declaration Calling for the Abolition of Nuclear Weapons at Mitsuzawa Stadium in Yokohama on September 8, 1957. I had just started at high school that year. Most of the 50,000 gathered that day were young people, but looking around, all generations were represented, even children accompanied by their mothers. President Toda declared that the use of nuclear weapons must be absolutely condemned under any circumstance in order to protect the inviolable right to live of the world’s people.

Over the years, every time I revisit the Declaration, one conviction always comes to mind: the catastrophe caused by nuclear weapons in Hiroshima and Nagasaki must never be repeated anywhere on the planet. It is the social mission of the Soka Gakkai to steadfastly work toward a world free from these weapons.

Looking at the world today, I am deeply concerned by the continued erosion of the dignity of individual life amid ongoing conflicts and civil wars, compounded by the threat of nuclear weapons, which is once more intensifying.

International humanitarian law was developed out of a shared and powerful recognition, following the immense devastation caused by World War II, of the need to protect civilians from the ravages of war. In his 2019 peace proposal, President Ikeda referred to the background leading to the adoption of the Geneva Conventions as follows:

“The Conventions—which formed the foundations for subsequent international humanitarian law—manifested this powerful determination precisely because the cruelty and tragedy of war had been acutely felt by the participants in the negotiating sessions.

“Unless we consistently revisit the origins of the Geneva Conventions, we will remain mired in the kind of arguments that justify as acceptable any action so long as it does not explicitly violate the letter of the law.”

It has been widely reported that international humanitarian law is being violated in the conflicts currently raging around the world. This is unacceptable. While acknowledging that an immediate and total elimination of war may not be feasible, I would like to call on all parties to take the eightieth anniversary of the end of World War II as an opportunity to reaffirm their pledge to uphold international humanitarian law. We should in particular remember that the postwar renewal of the Geneva Conventions was motivated by calls to establish safe zones for children, women, the elderly and the sick and wounded.

A Vow to End All Suffering

We, the members of the Soka Gakkai, strongly urge that the “bulwarks against war”—whereby divisions and conflicts are prevented from escalating into full-scale military clashes—be reinforced through the solidarity of the people. This is what President Ikeda consistently advocated throughout the annual peace proposals he issued for forty years spanning 1983 to 2022.

In his second peace proposal in 1984, he stressed: “It is vital that we both deepen and broaden our efforts for disarmament and, at the same time, fortify our ongoing commitment to creating a world without war.” It was the shift in both these dimensions—the growing diplomatic momentum toward disarmament and rising grassroots voices calling for peace—that helped accelerate the end of the Cold War.

Today, we are witnessing around the world a normalization of the use of military force and the civilian casualties that result; what is needed at this juncture is that we once again redouble efforts in the two crucial dimensions highlighted above.

In 2015, marking the seventieth anniversary of the end of the war, President Ikeda made a deeply memorable proposal to the Soka Gakkai youth division on the significance of the renunciation of war. He called for the annual Peace Summit that had long been organized by the youth division members of Hiroshima, Nagasaki and Okinawa to be relaunched under the name “Youth Summit on the Renunciation of War.”

Why did he choose the phrase “renunciation of war” rather than simply “peace”? His true intention had been expressed in his peace proposal that year:

“There is no one who would find violence or oppression based on prejudice directed at them or their families acceptable. But when it is directed at other ethnicities or populations, it is not unusual for people to consider it justified by some fault or failing on the part of the victims. To prevent such situations from escalating, the first step is to develop the means of bringing oneself face to face with the other, free from this kind of collective psychology. . . .

“Without such efforts [to understand the other and see things through their eyes], particularly in times of heightened tensions, it is all too easy for our own ideas of what constitutes peace or justice to become a threat to the lives and dignity of others.”

In today’s world, the term “peace” is all too often divorced from its original meaning and used instead as a pretext to legitimize aggression and violence. President Ikeda’s key message here is that, rather than allowing this distortion, we must deepen our commitment to peace by making an explicit vow to renounce war, grounded in the conviction that no one on this planet should ever have to endure its horrors.

Given that the threat of nuclear weapons is becoming normalized in today’s world, I think that an urgent task facing humanity is to raise global public opinion calling for their non-use, thereby fortifying momentum toward their prohibition and abolition, and to take collective steps toward making this a century defined by the renunciation of war.

We must deepen our commitment to peace by making an explicit vow to renounce war, grounded in the conviction that no one on this planet should ever have to endure its horrors.

In light of this, we, the members of the Soka Gakkai, hereby declare our commitment to continue wholeheartedly addressing challenges in three key areas:

The first is youth exchange. Just as we humans are the ones who start wars, we are also the ones capable of overcoming division and confrontation to prevent conflict. Essential to this is building a society resilient to collective psychology and violent agitation.

We have long promoted grassroots exchanges, especially among youth, with our Asian neighbors including China and South Korea. We firmly believe that friendships forged by the youth of the next generation will serve as the most powerful foundation for a bulwark against war. Ensuring that each new generation experiences such exchanges is key to creating a society that rejects war.

The second area is interfaith dialogue. There can be no question that throughout the history of humanity differences in religion have often given rise to serious strife. At the same time, many religions have provided vital spiritual sustenance to those seeking peace and dignity. Bearing both of these factors in mind, people of faith must take concrete action to build a better world, and expanding dialogue to deepen mutual understanding will ensure that the mistakes that have time and again led to discord are not repeated in the future.

Last May, I went to the Vatican City to meet with Pope Francis to discuss the urgent need to realize a world without war and free from nuclear weapons. This June, I also exchanged views with Prof. Datuk Dr. Abdelaziz Berghout, Dean of the International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilisation at the International Islamic University Malaysia, on the peace philosophies articulated within Buddhism and Islam.

Both the Soka Gakkai and Soka Gakkai International (SGI) have engaged in dialogue with other faith-based organizations (FBOs) at United Nations meetings and various forums, and these have resulted in the issuing of joint statements on matters of shared concern. We will continue to pursue interfaith dialogue actively in the years ahead.

The third area is the expansion of a global solidarity—people working together to solve the challenges facing the world. Collaborative efforts toward shared goals provide the strongest foundation for establishing trust that transcends national and ethnic differences. This insight has been deeply reinforced through our work on supporting the United Nations’ initiatives to address global issues such as human rights and climate change.

Now more than ever, the international community must pivot from an era where mutual mistrust has led to the buildup of military arsenals to one in which nations work together to tackle common threats and challenges facing humanity. As we make steady progress toward this transition, the path toward a century defined by the renunciation of war will inevitably come into clear view.

President Ikeda once quoted Shakyamuni’s words, “Putting oneself in the place of another, one should not kill nor cause another to kill,”3 and emphasized:

“We are, by virtue of being human, endowed with the tools that we need for this pursuit: the tuning fork of self-reflection with which to imagine the pain of others as if it were our own; the bridge of dialogue over which to reach out to anyone, anywhere; and the shovel and hoe of friendship with which to cultivate even the most barren and desolate of wastelands.”4

Upholding this spirit, on this eightieth anniversary of the end of the war, together with our fellow members in 192 countries and territories worldwide, we reaffirm our unwavering determination to continue taking action to build a century in which war is renounced and all people can live in peace and dignity.

- *1Daisaku Ikeda, Journey of Life: Selected Poems of Daisaku Ikeda (New York: I.B. Tauris, 2014), p. 348.

- *2Translated from Japanese. Daisaku Ikeda, “Haha to naru koto” (Becoming a Mother), Josei Sebun, April 28, 1969.)

- *3Acharya Buddharakkhita, trans., The Dhammapada: The Buddha’s Path of Wisdom (Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society, 1996), p. 53.

- *4Daisaku Ikeda, Compassion, Wisdom and Courage: Building a Global Society of Peace and Creative Coexistence, Peace Proposal, January 26, 2013.