The Oneness of Mentor and Disciple

In any field, a person who aids the development of another may be regarded as a mentor. In Buddhism, which is concerned with human happiness and development, the mentor-disciple relationship is fundamental. The foundation of the relationship between mentor and disciple in Buddhism is the shared pledge to work together for the happiness of people, to free them from suffering.

The Lotus Sutra, the Buddhist scripture that is the basis of Nichiren Buddhism, contains a vivid allegorical description of the moment when the Buddha’s disciples make this pledge. The sutra describes how, during an occasion when Shakyamuni Buddha is preaching, the earth splits open and a multitude of resplendent bodhisattvas (individuals who have made compassionate action the foundation of their being) emerge. These so-called “Bodhisattvas of the Earth” are firmly resolved to continue to live out Shakyamuni’s teachings after his passing, in the difficult and corrupted age to come. They vow to exert themselves to save people from suffering in this period of great social and spiritual turmoil, facing head-on whatever hardships they may encounter.

This grand, cinematic description portrays the profundity of the shared commitment of mentor and disciple to working for people’s happiness throughout time. It is a metaphor for the transformation of the Buddha’s disciples from passive recipients of the teachings to people committed to advancing on the path of compassionate action pioneered by the Buddha.

Defining a Path

Buddhism is a philosophy with the aim of empowering people. Its central premise is that each person has the innate capacity to triumph in any circumstances in which they find themselves, to surmount any source of suffering, transforming it into a source of growth and strength. It is a philosophy established on the conviction that there exist within the lives of each of us at each moment inexhaustible reserves of courage, wisdom, compassion and creative energy.

The mentor makes the disciple aware, and continues to remind him or her, of this profound potential, giving the disciple confidence in their own unrealized possibilities. It is the mentor’s own life, at least as much as their teaching, that provides this inspiration. The abstract ideal of enlightenment is made tangible in the mentor’s character and action.

The mentor’s life is focused on the empowerment of others, modeling the fact that our own highest potential and happiness are realized through taking action for others. As Daisaku Ikeda writes, “The enlightenment and happiness of both self and others: A true mentor in Buddhism is one who enables us to remember this aspiration.”

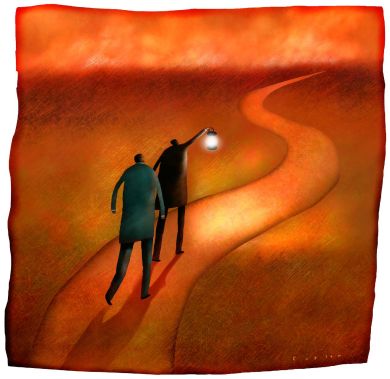

The path of developing one’s own humanity that Buddhism maps out—the “path of enlightenment”—lies in the balance of having the courage to squarely confront one’s own challenges, striving to grow and develop as a person, while taking action for the sake of others. At a crucial moment of indecision, thinking of a mentor’s example can help one take a courageous step and break through one’s limitations. The mentor’s teachings and example help the disciple continue to progress on this difficult path of enlightenment—difficult because of the powerful countervailing tendencies of the human heart toward complacency, fear, arrogance and laziness. Ikeda comments: “A mentor helps you perceive your own weaknesses and confront them with courage.”

That the mentor is a model of Buddhist practice does not mean that the disciple strives to imitate the mentor’s persona, but rather to learn from the mentor’s example, or way of life, and to bring that approach to life to bear on their own particular circumstances, expressed through the qualities of their own unique character. It is by internalizing the mentor’s spirit in this way that the disciple grows and develops beyond their self-perceived limitations. The mentor-disciple relationship in Buddhism is a courageous path of self-discovery, not imitation or fawning.

In Buddhism, ultimate responsibility lies with the disciple. The mentor is always prepared to teach. The disciple must choose to seek and learn, and will develop to the extent that he or she works to absorb and take action on the basis of the mentor’s teachings.

A Genuine Mentor

What criteria distinguish a genuine mentor in Buddhism? First is the fundamental orientation or motivation of the teacher—the ideal to which that person has dedicated their life. The highest, most noble ideal is the commitment to enable all people, without exception, to overcome suffering and become happy. Furthermore, a genuine teacher is one whose own efforts to seek truth and develop wisdom are continual throughout their lives. This attitude could be contrasted with that of a teacher who believes they have learned all they need to know and need only dispense their knowledge in a one-sided manner. That kind of teacher is also likely to try to boost their standing by obscuring the truth and turning knowledge into a privilege, rather than making it freely available to all.

The ultimate desire of a genuine mentor is to be surpassed by their disciples. This open-ended process of growth and succession is what allows a living tradition to develop and adapt to changing times. In the Lotus Sutra, it is signified by the fact that the Bodhisattvas of the Earth are even more splendid in appearance than their mentor, Shakyamuni.

Defining the respective functions of mentor and disciple, one could say that the role of the mentor is to point toward an ideal and the most effective means of its achievement, while the disciple strives to realize this ideal on an even greater scale than has been achieved by the mentor.

The shared ideal, and the shared struggle to realize it, create a profound closeness in the lives of mentor and disciple—what Buddhism describes as the “oneness” of mentor and disciple. This is the lifeblood of Buddhism and the means by which the aspiration to live a fully realized life and enable others to do the same is transmitted and developed from one generation to the next. In the absence of this shared commitment and the effort on the disciple’s part to strive in the same spirit as the mentor, the mentor would simply become an object of veneration and Buddhism would lose its transformative power.

Growth and Continuity

The deep connection between mentor and disciple, and in particular the relationship between the Soka Gakkai’s first three presidents, is what has sustained the development of the organization. Each successive president has expanded on the vision of his predecessor in painstakingly developing a movement able to reach out to, embrace and empower the greatest diversity of people. Daisaku Ikeda (1928–2023), third Soka Gakkai president, worked closely with second president Josei Toda (1900–58) in the post-World War II period to empower literally millions of Japanese people, enabling them to positively transform their circumstances. Toda himself had been imprisoned alongside his mentor, founding president Tsunesaburo Makiguchi (1871–1944), for refusing to compromise the integrity of the teachings of Buddhism under pressure from Japan’s militarist government.

Ikeda has broadened and internationalized the vision of people’s empowerment he inherited from these mentors, taking it beyond the scope of a religious movement and developing a global movement for the promotion of peace, culture and education.

Ikeda has described his actions as an effort to inspire others with a sense of the possibilities that one person can accomplish on the basis of the mentor-disciple spirit. He has frequently expressed his determination to open new avenues for engagement with social and global issues that can be fully developed by future generations. “The relationship between mentor and disciple,” he writes, “can be likened to that between needle and thread. The mentor is the needle and the disciple is the thread. When sewing, the needle leads the way through the cloth, but in the end it is unnecessary, and it is the thread that remains and holds everything together.”

The commitment to the happiness of all people is at the heart of Buddhism. But it is through the relationship of mentor and disciple, through life-to-life connections, one person’s aspiration igniting another’s, that this ideal is brought out of the realm of abstract theory and made a reality in people’s lives.

Courtesy January 2010 issue of the SGI Quarterly.